The memories of others

11 years ago, on June 5, 2014, Mosul fell to ISIS. What was a complete rupture in the lives of the inhabitants of the city was a mediatized news event for people around the world, including myself. When so many pairs of eyes look at a tragedy, one should assume every detail is preserved. Media reports and academic literature on military failures and ISIS strategies were quickly produced. What seemed to be left out were the memories of the citizens.

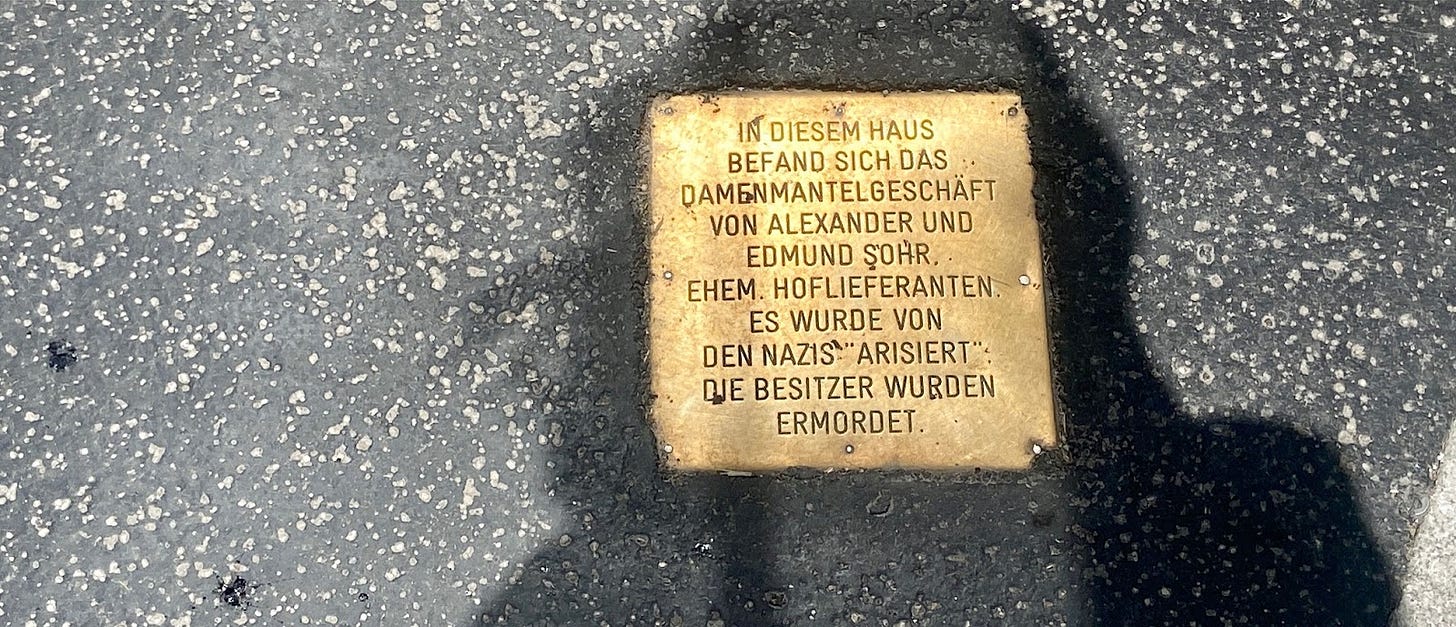

Image 1. ‘Stolperstein’ in front of Schauflergasse 2, 1010 Vienna, Austria. The text reads: “In this house, the shop for women’s coats by Alexander and Edmund Sohr, former purveyors to the court, was located. It was “Aryanized” by the Nazis. The owners were killed.”

I am in the incredibly fortunate position of never having witnessed war myself. I only read about it, watched movies on wars, and listened to the rather sparse stories from my German grandparents. On the rare occasions they spoke about that time – in my memory: mostly about being hungry – even as a child I felt like these memories carried weight, these memories had to be listened to. The narrations filled me with awe because I knew I had to remember them to eventually pass them on.

I only know war through the memories of others. I inherited memories of war and fit them into the context that history books provided. To me, remembrance of war became a civic duty. And with this duty, the question of what must be remembered and how it should be remembered slowly transferred to me. Yet, I do not know what parts of the storyline my grandparents wanted me to keep. I fear that I lose aspects of these memories, an emotional access I never had myself. My approach is almost technical. I try to think about it conceptionally, hoping that this helps me to carry the duty of preserving the memories of others responsibly.

How we remember war

Memories of violence and war exist around the globe, shape personal and national identities, and characterize political discourse – explicitly or implicitly. Official commemoration ceremonies formed into a ritual by state officials, memorials that we walk past without knowing, the anonymity of history books in school. These memories are always fragments of larger stories, they are told asynchronously, and confront us at different times and in different situations.

“You will always recognize the Germans by whether they refer to May 8 as a day of defeat or liberation.” (Heinrich Böll, German writer, in 1985, about May 8, 1945)

These memories are also contested – not only when new documents are discovered but also when socio-political tides change. Narratives once assumed to be common knowledge suddenly become disputed. Personal stories narrated by others may contradict each other, or will always give the impression that important elements are missing.

And it is not only the memory of violence itself that is contested; also how violence is commemorated will be debated – even more so in the case of the atrocities of genocide. A number of memorials built in remembrance of the Holocaust have sparked and continue to spark debates. As of 2024, 107,000 golden ‘Stolpersteine’1 (German for ‘cobble stones’ or ‘stumbling stones’), created by artist Gunter Demnig, confront passersby on streets across European cities and remind them of the individual victims of Nazi Germany. Some voices criticize the laying of these stones as not being a dignified, worthy form of remembering the victims of Holocaust.2 Others emphasize the value of precisely these small stones for remembering the individual suffering as compared to the statistical number of victims that all too often glosses over their personal fates.

How and when we remember and the forms we deem suitable for such remembrance will vary. Some will not want to remember, some are eager to discover every detail. To some, speaking to individuals not involved or affected by the tragedies may be easier, to some it may be even more difficult. The kinds of memories one holds seems to shape the forms chosen for their preservation.

Image 2. ‘Stolperstein’ in front of Petersplatz 3, 1010 Vienna, Austria. The text reads: “In this house lived: Friederike Grünwald, born March 1, 1872. Deported to Theresienstadt in 1942. Killed in Treblinka on Sept 26, 1942. Arpad Grünwald, born December 6, 1896. Deported from Malines to Bergen-Belsen in 1944. Death on January 13, 1945, in Natzweiler.”

As someone with only second-hand memories, I try to support remembrance, not decide about its forms. I try to understand the technicalities of remembrance to ensure all kinds of memories and all kinds of forms of remembering find their places.

“What must we not forget?”

All these different ways of remembering, from the ritualized state ceremonies to the spontaneous narrations transmitted by relatives, may be summarized under the term ‘culture of remembrance’ or ‘memory culture’. In simplified terms, Jan Assmann, Professor for Egyptology, has described memory culture as the answer to the question: “What must we not forget?”.3 He describes it as a phenomenon inherently tied to a specific social group and its past. Sharing a culture of remembrance may even be the constitutive element of a community.

While an outsider's perspective may be valuable at times, the question “what must we not forget?” clearly directs the focus to the community affected. Remembrance culture is based on the results of their analysis of the past, their involvement with it.

Assmann mentions two central preconditions for memory culture: First, the past must have been documented, it must be accessible in some form. Second, there must be some discernible difference between the group’s past and present. A break that ‘produces a past’, for example through the use of different language that marks that break.

Yet, this past does not automatically turn into history, into a linear storyline, clearly structured and commonly agreed upon. In order for a memory to enter the culture of remembrance of a certain community, it must be formulated in concrete words. In reference to the work by the sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, Assmann writes: “Memory (...) works through reconstruction.”4 One creates it. It is a process that, at the same time, structures how a group thinks of their past and their future. He specifies: “Thus collective memory operates simultaneously in two directions: backward and forward.”5 Not only does this imply that a culture of remembrance needs active work but it also highlights its enormous impact on the future of a community.

A culture of discourse

There are only two things I know about remembrance of war: it is difficult and it is necessary. In many ways, it defines us. The question of “what must we not forget?” is incredibly large – and it will never be fully and comprehensively answered. Different generations will have different answers. However, at its core, the question invites discourse. A culture of remembrance cannot be established by a single actor – or by a media outlet – it is the result of the discourse within a community, among first-hand memory narrators and second- and third-hand memory keepers.

Remembrance takes time and challenges us. It is fragmented and contested. It neither has a defined beginning nor an end date. The sometimes arduous task of collecting, analyzing, and interacting with stories, documents, and photos from a group’s past is a necessary step for remembrance to flourish.

See, for example, an article by Deutschlandfunk Kultur on the critcism voiced by the Swiss artist Dessa (https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/schweizer-kuenstlerin-dessa-stolpersteine-in-der-kritik-100.html), or an article by German newspaper taz on the controversies surrounding the stones in the city of Munich (https://taz.de/Stolpersteine-in-Muenchen/!5324372/).

Assmann, Jan. 2012. “Cultural Memory and Early Civilization. Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination”. Cambridge University Press, p. 16.

Assmann 2012, p. 27.

Assmann 2012, p. 28.

”Only thank God men have done learned how to forget quick what they ain’t brave enough to cure.” William Faulkner, The Hamlet